By Conor Casey

Growing up an Irish Catholic, there was a uniformity in almost every other Catholic home I’d visit. Above every fireplace sat a picture of Pope John Paul prominently displayed next to a collectors plate of John F. Kennedy. As the first Catholic president, the significance of Kennedy’s ascension in American politics cannot be overstated—for many immigrant families it signified the end of over a century of marginalization. It wasn’t until JFK’s inauguration that many Catholics felt they had made it and after so many years were finally seen as Americans themselves.

Kennedy’s candidacy was not met with the same acclaim in some communities, and many felt that by voting in a Catholic president, they would be handing the keys of the White House to the Vatican. The group Citizens for Religious Freedom wrote at the time, “it is inconceivable that a Roman Catholic President would not be under extreme pressure by the hierarchy of his church to accede to its policies with respect to foreign relations…and otherwise breach the wall of separation of church and state.” In Washington, 150 Protestant ministers met to declare that he could not remain independent of the Church and demanded he publicly denounce their teachings.

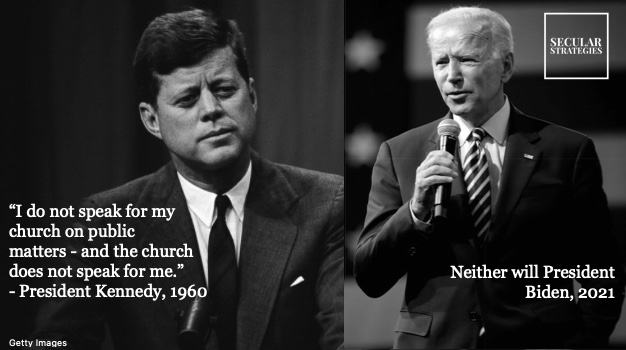

Kennedy was eager to prove them wrong and many credit his historic win with his incredible ability to win over powerful Protestant strongholds and confronting the issue of religion in politics head-on. “Contrary to common newspaper usage, I am not the Catholic candidate for president,” he said at a Southern Baptist conference in Texas. “I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me.”

He was true to his word, and over his tragically short term in office made a point to never let his personal faith drive his agenda, paving the way for other Catholic politicians to win office. While abortion was not a hot-button issue of the time, and Kennedy was personally opposed to abortion, he would appoint Justice Arthur J. Goldberg, the son of Jewish Ukrainian immigrants, to the bench—Goldberg would later be pivotal in invalidating a 1965 state anti-contraceptive law on the grounds it interfered in the right to privacy, a right later used to justify legalizing abortion in Roe vs. Wade.

While many at the time feared JFK would be too beholden to his church, today President Biden faces criticism that he is not beholden enough. The Church’s very public targeting of Biden is a departure from past practice that sets a dangerous tone for any Catholic seeking office—you’re either with us or against us.If we are to be appalled by the influence of money in politics today, the idea of holding an elected official hostage over their personal faith should be reprehensible. Certainly, the Church has every right to determine who receives Communion, but it is completely improper for a group of activist bishops to politicize and weaponize the Eucharist as if it were an article of the Constitution.

The debate over who can or cannot receive Communion has spilled out of cathedrals and into the halls of Capitol Hill, with Catholic politicians inappropriately using their official capacities to influence the Church’s policy on Communion. In the same breath as they exalt the separation of church and state, they describe how “faith influences them as lawmakers, making clear their commitment to the basic principles at the heart of Catholic social teaching and their bearing on policy.” They miss the point that by issuing an official statement on behalf of Catholic lawmakers, they cross the very line that they purport to value.

Today, I sit under one of the same Kennedy plates I remember seeing in my childhood and admire the precedent he set when he said, “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.” It was then that he became a president not only for us Catholics, but for everyone. The current debate is a stain on his legacy, threatening the separation of church and state and opening the doors to a new age of division and bigotry.